Digitizing Mathare Valley With Africa’s Largest Mesh Network

By Nivi Sharma & Loyce Chole

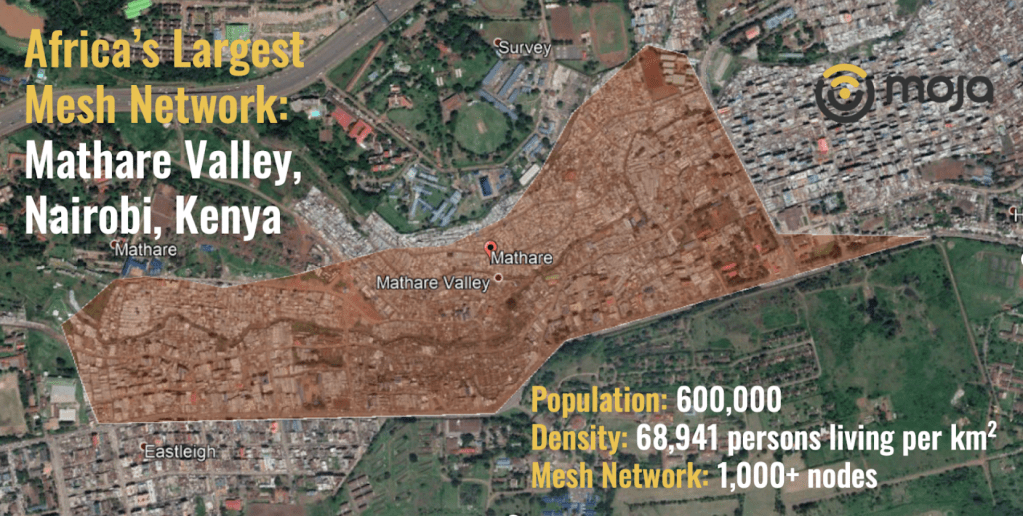

Mathare Valley is one of the oldest, poorest, most densely populated slums in the world. Despite having over 60,000 people living per km2 (in contrast to the national average of 82 persons per km2), many people in Kenya are not aware of the poor living conditions in the region. It’s rare for people in the rest of the world to even know about Mathare Valley, let alone understand the impact of the digital divide on their livelihoods.

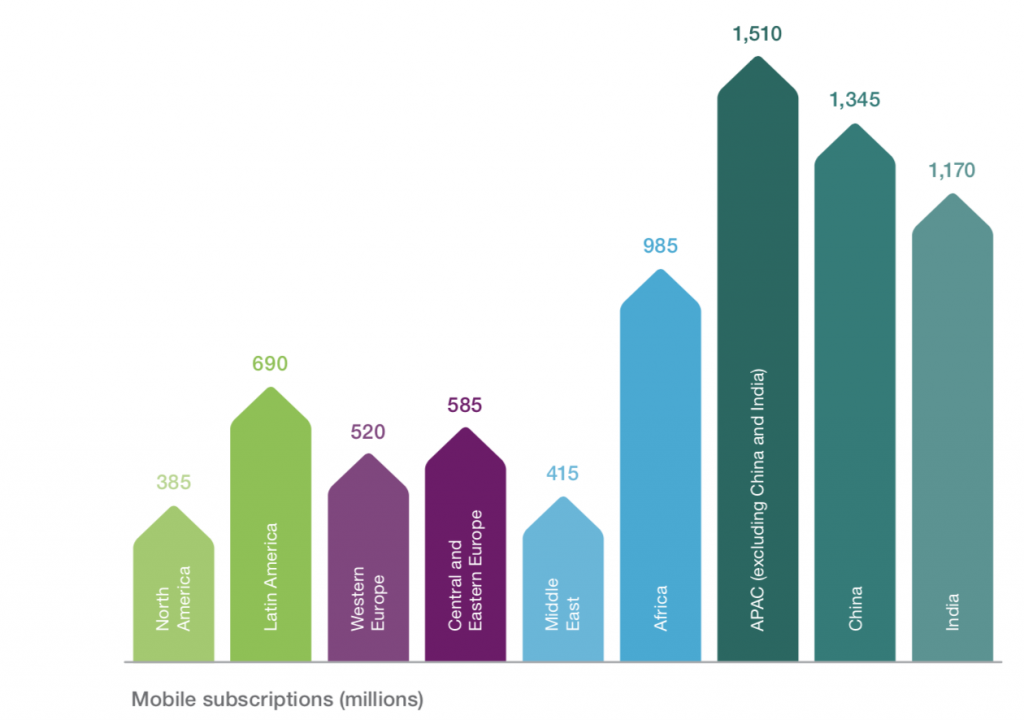

BRCK has connected more than 2 million people to the internet over the past 3 years. This year, we have embarked on a bold and ambitious project in partnership with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Within the framework of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) funding program develoPPP, GIZ and BRCK joined forces to bring Moja free WiFi to Mathare Valley. The partners are installing a technical infrastructure that connects the entire slum population of at least 600,000 people. This infrastructure is the largest mesh network in Africa where residents are able to access the internet at no direct cost. Using their smartphones, users perform digital tasks on the Moja platform like watching an ad or filling out a survey to earn Moja points that they can then use as credit to access the internet. Moja is also a repository for health and education information that is disseminated to residents, helping them cope with the economic impacts of the pandemic.

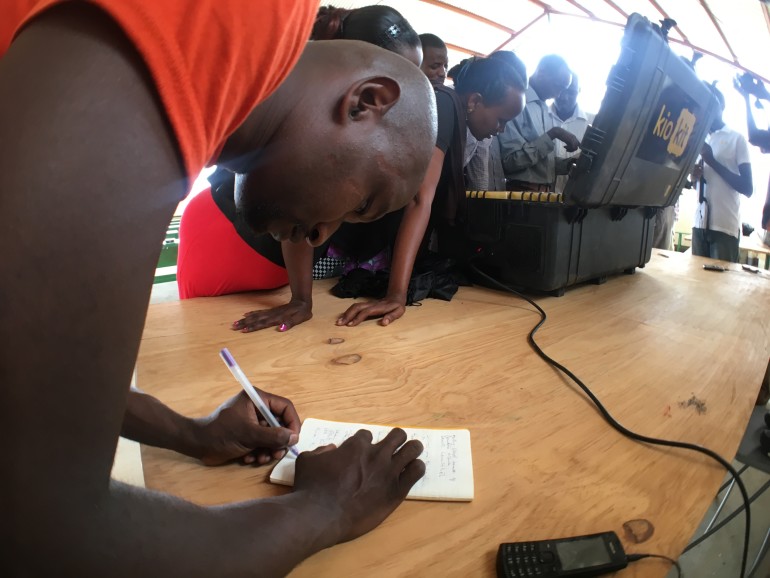

5,000 SMEs and entrepreneurs are being trained by our partners, Shining Hope for Communities (SHOFCO). SHOFCO, is a Kenyan, grassroots non-profit that aims to build urban promise from urban poverty. SHOFCO are training Mathare business owners on how to leverage the free Internet service to unlock the potential of digital access to jump start or grow their businesses; and digital services to gain business skills as well as take advantage of government and social services. A further 5,000 residents of Mathare will be trained on basic digital skills giving them the tools to participate in the global economy.

BRCK’s innovation lies in using mesh technology to improve network coverage and resilience in Mathare by allowing access points to intelligently connect to each other and fail over in case of network issues. In order to provide high quality, affordable connectivity, BRCK has developed the SupaMESH WiFi Access Point. This device has been co-created by BRCK, Ignitenet and Facebook Connectivity to enable large mesh networks (>100 Sites) in challenging environments.

Deploying and maintaining a network infrastructure in Mathare Valley is not without challenges. Power is a major issue at most sites – it’s neither reliable, nor clean. Theft and vandalism are also a risk we foresee. However, having rolled out a quarter of the planned network so far, we see how much the youth value the service and we’re confidently counting on them to continue to protect the “bright yellow WiFi squares” that have dotted the Valley. We are especially grateful for the support from Community Based Organizations and Youth Groups like Mathare Social Justice Centre, Pamoja Twaweza Community Project, Shantit and Muoroto.

One of the biggest concerns that young people brought to BRCKs attention was that there are not enough points earning activities for them. In short, they want more digital tasks on the platform from organizations who value their time or their eyeballs. These are the first important steps towards giving the youth the opportunity to earn from real digital work: we are encouraging all organizations interested in engaging with these young people to think creatively about leveraging the Moja platform: advocacy and awareness campaigns; short polls and long surveys; and brand awareness. With Moja WiFi, the youth of Mathare Valley now have the opportunity to be active participants and beneficiaries of the digital economy.